One of the themes that came out of the second popularising palaeontology workshops was the democratic access to knowledge around palaeontology. In my presentation ‘What has palaeontology ever done for us?’ I aimed to show that popularising palaeontology and making ideas accessible is laudably ingrained in the discipline. From schools outreach, museum displays and exhibitions, social media, fieldtrips for the public, fossil festivals, documentaries and popular science books many palaeontologists undertake these activities as part of their role, normally giving up a lot of their own time to do so. Popularising palaeontology is also part of the formal training for many palaeontology students, certainly in the UK, as evidenced by the enthusiastic undergraduates and postgraduate students communicating their work at fossil festivals and on social media. Many natural history museums were founded on the principals of sharing information for the common good, previously under the guise of ‘betterment’ (with a dash of social status boosting for founders of these early institutions) and today part of public engagement and public engagement with research.

However, pursuing an interest in palaeontology is still a luxury activity for most. Visiting museums, picking up the latest popular book on dinosaurs or watching a documentary are all activities competing for people’s ‘free-time’. As a museum professional, I’m interested in trying to assess what information people bring with them. Where are the baselines for knowledge that can help us plan and pitch interpretation, tours, events and blog posts? Pitch it too high and you could end up baffling or alienating audiences (and it’s already a big challenge to get people through the doors of intimidating museum spaces). Pitch it too low and you miss the opportunity for transformational learning, although there is a debate about if engaging with museums should purely be for learning/education or not.

That the public know anything about palaeontology in the first place, is in itself a testament to the success of a couple of centuries of popularising palaeontology. There’s very little that we can expect everyone coming through the doors of a museum to know when it comes to palaeontology. In the UK there’s not much in the national curriculum directly dealing with the subject and curriculum taught content at schools is a great equaliser in that, with exceptions, people of all classes and backgrounds are exposed to the same(ish) content. At GCSE and A-Level, students start to choose their own curriculum or leave school altogether. Of course there may be some who choose geology A-Levels or even pursue degrees in earth sciences but as a portion of the overall population this is a diminishing number of people.

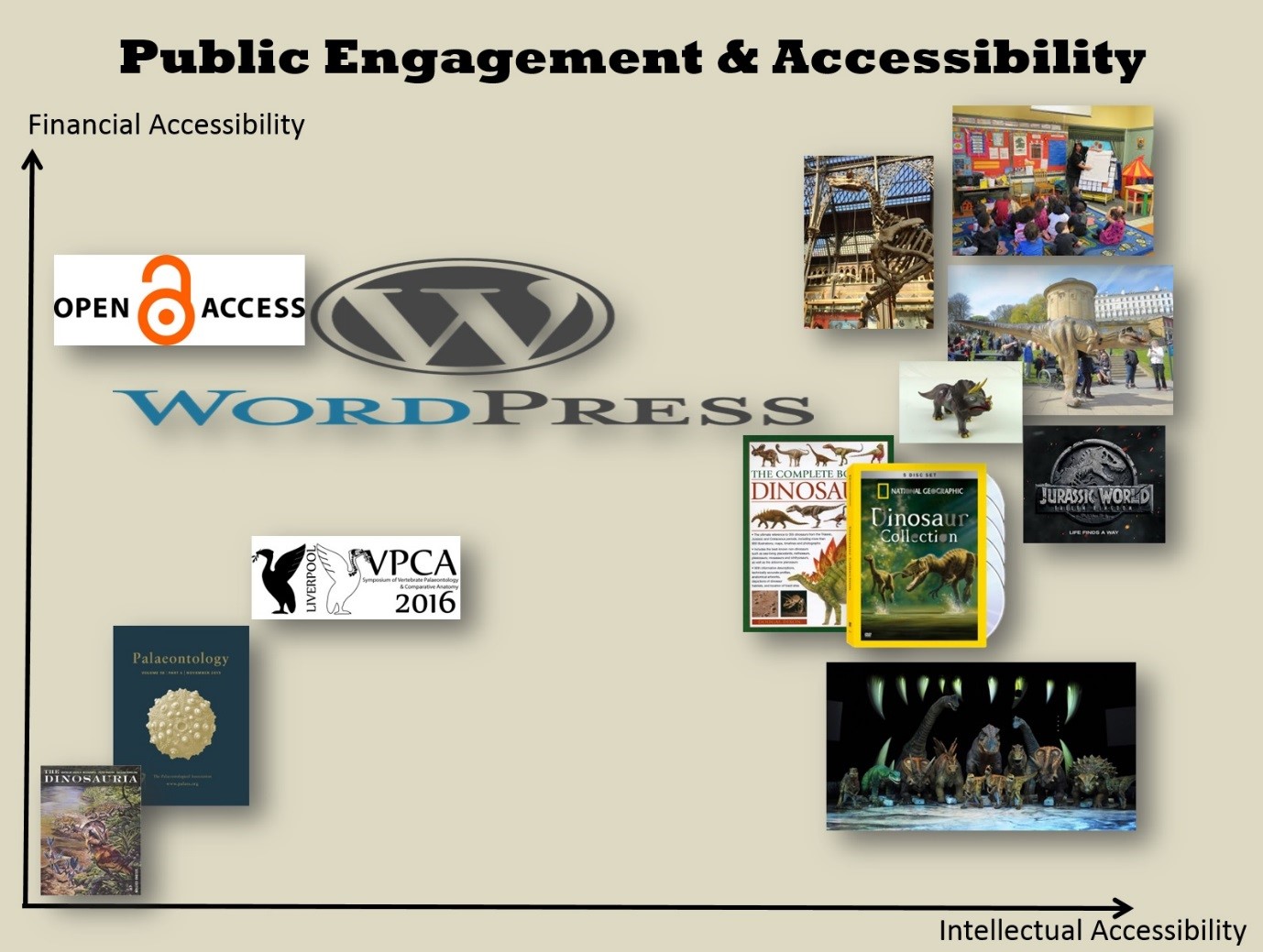

So where do people get access to palaeontological information beyond what they may learn at school and how can this inform how museums engage them with palaeontology? A bag of a fag-packet analysis might look at how readily available information is in terms of financial accessibility as well as intellectual accessibility. The idea behind the below figure I presented at the workshop. Of course, there are many more aspects to consider than these but in thinking about a baseline for the information people are likely to bring with them we can expect that more democratic sources of palaeontological information are more widely taken up. For example, it’s reasonable to assume that fewer people splash out on extremely expensive technical palaeontological texts costing hundreds of pounds than visit museums or go to the cinema to see Jurassic World.

Plotting the financial and intellectual accessibility of palaeontological outputs.

This is where we hit a tension that has been another major theme of the Popularising Palaeontology workshops, accuracy and authority of available palaeontological information. Jurassic World is famously, misrepresentative and inaccurate and obviously not intended as a palaeontological text, but as a piece of entertainment it requires the cost of a cinema ticket to access. Many palaeontologists are frustrated that such an impactful piece of media doesn’t take the extra care to get things right but then that’s the conflict between the goal of movie producers and the goal of science communicators. In any case, people do take the information they get from movies like Jurassic World and fold it into their general knowledge about palaeontology, hence questions like “Can we bring dinosaurs back from extinction?” that anyone who has staffed a stall at a fossil festival will undoubtedly have got.

In the museum context, the nature of palaeontological specimens also presents issues unlike perhaps social history, art and archaeological collections. Irrespective of education, artifacts such as paintings, sculpture, ceramics or coins are more easily understood as human made objects. The panoply of palaeontological specimens are less intuitively understood from the casts or composites dinosaur skeletons through to the complex variety of different kinds of fossils.

So we have very little assurances when it comes to the palaeontological information that the public bring with them into museum spaces. It’ll be a mix of information from children’s books, movies, documentaries, science reporting in the mainstream media, toys, games and maybe a Wikipedia article or two.

This presents a significant challenge for public engagement in museums both in terms of the range of content that is covered as well as the level. Ideally we’d pair up each visitor with their own expert palaeontologist and science communicator who could react to questions and queries and run them around the museum offering bespoke tours and trails pitching the content precisely at the needs of the individuals. For obvious reasons, it’s the proxies of museum labels and interactives which do most of the heavy lifting when it comes to communicating science to the public which is precisely why there’s a perpetuating cycle of subjects and topics covered in museum displays. Most natural history museums will likely have a dinosaur, human evolution and perhaps ‘Ice Age mammals’ gallery or display. Few will give the same space and attention to archaeocyathans or mollusc evolution even when, on paper, there is a rich science behind all of them. It’s why displays called ‘These Are Not Dinosaurs’ highlighting pterosaurs, plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs are still present (and needed) in museums as a direct response to the fuzzy public conflation of all these charismatic extinct animals.

So how do we break the cycle or do we need to? Well fortunately, museums do have a lot of agency in steering this as intellectually and financially (more so in some parts of the world) accessible, trusted spaces with millions of visitors a year. With a bit of creativity we can employ some of the tools we use to push dinosaurs to shed light on other areas of palaeontology. Instead of buying another Stan or Sue, commission a life-size Cameroceras model or a diorama of an Ordovician reef. Smart technology also has a better part to play in museums than is currently being employed. I’d like to see displays that link through to relevant articles, papers and blog posts to give visitors the opportunity of exploring more and to kick start self-directed learning. We may not have enough expert guides for each and every visitor but livestreams, videos and podcasts are surely less of a compromise than static interpretation with a choice fact or two.

By straying beyond the well-worn paths we’ll undoubtedly inspire film makers, scientists of the future, authors and museum visitors to explore these subjects more. This has happened a few times in the past. Virtually every natural history museum will have the same set of horse fossil casts on display which can be traced back to George Gaylord Simpson’s work on fossil horses. The same can also be said of Bernissart Iguanodon specimens, Archaeopteryx and the Oxford Dodo. Interestingly, all of these examples stem from museums sharing objects and casts of objects with each other. With 3D visualisation and printing so readily to hand these days, rather than retread the tropes of popular palaeontology we should be looking at creating palaeontological tropes of the future which, hopefully in turn ends up as part of the baseline public consciousness around palaeontology.